Take a short scroll through your Facebook feed and you’re bound to hit a post titled “10 Habits of Highly Likable Junior Executives” or “19 Phrases You Use that Make Your Boss Want to Fire You and Make Your Family Wish that You Didn’t Have a Mouth” or “8 Things You Must Do Before Noon if You Want to Achieve More than Nothing.” I used to drink these articles in when they popped up, but eventually I grew weary of the conflicting advice. For example, if I want to be a better writer, I should write in bed, because that’s what Mark Twain did. Or maybe I should write standing up, because that’s how Ernest Hemingway did his best work.

Why did I fail to achieve habit enlightenment even though Fast Company told me I should wait to check my email until 11am? And why did I continually fail to remember names, even though Forbes explained that this is an essential trait of respected leaders? The reason, says habits expert Gretchen Rubin, is that before you can form better habits, you must first grasp how you yourself form habits in the first place.

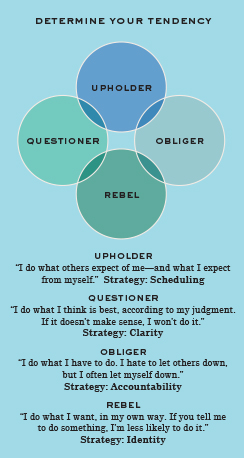

On an episode of the Unmistakable Creative podcast, Rubin said that there’s no silver bullet when it comes to habit-formation motivation, but a little introspection goes a long way. In her latest book, Better Than Before: Mastering the Habits of our Everyday Lives, Rubin lays out a framework for understanding our unique motivations for meeting expectations, and how our motivations are linked to our identities. The framework, called “The Four Tendencies,” is described in this infographic:

To find out where you fall, take the quiz. And be honest: selecting the answers you think sound ideal won’t help you better your habits.

Spoiler alert: According to Rubin’s research, most of us are Obligers, with Questioners making up the next largest group. Upholders and Rebels are rare. I’ve found this to be true on a tiny personal scale, too. 8 out of 10 people that I’ve quizzed are Obligers. This makes sense, since so many of us say that we never make any time for ourselves.

At first, this Venn diagram looked pretty grim for a Rebel like me. How could I hope to form a positive habit while resisting inner and outer expectations? Rubin says that for Rebels, it’s all about identity; if a habit jibes my idea of who I am, it’ll stick. This certainly resonates with me, and in fact Rubin says that people of each Tendency are guided in part by what they hold to be essential to their identities. This can be problematic, however, if identity is linked to a bad habit or prevents the adoption of a good one. For example, someone who identifies as meat-and-potatoes guy might be preventing himself from feeling happier and healthier by expanding his diet. As Rubin notes, quoting Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, “But then one regrets the loss even of one’s worst habits. Perhaps one regrets them the most. They are such an essential part of one’s personality.”

You don’t have to have Hemingway’s habits to be a genius writer; I mean, do you really feel like adopting dozens of polydactyl cats? Instead, first try to understand how you are motivated to form habits, using a tool like Gretchen Rubin’s Tendencies. To learn more about it, check out her blog or send this Rebel an email.